How to Overcome Procrastination with ADHD or Anxiety: Evidence-Based Solutions

Author: Dr. Timothy Rubin, PhD in Psychology

Originally Published: November 2025

Last Updated: November 2025

Procrastination with ADHD or anxiety isn't about laziness—it's about how your brain processes emotion, urgency, and overwhelm.

Contents

- Why ADHD Makes You Procrastinate

- Why Anxiety Fuels Procrastination

- 7 Evidence-Based Strategies to Stop Procrastinating

- When to Consider Professional Help

- Frequently Asked Questions

Procrastination can feel impossible to overcome when you're living with ADHD or anxiety. The tasks that others breeze through might leave you feeling stuck, anxious, or overwhelmed. But here's the key thing to remember: you're not lazy—procrastination often stems from genuine neurological and psychological hurdles, not lack of willpower.

Research shows that procrastination is fundamentally an emotional regulation issue rather than a time-management problem. People procrastinate to avoid negative feelings like fear, boredom, or overwhelm—and when you have ADHD or anxiety, these emotional hurdles are amplified.

This guide explores why ADHD and anxiety make procrastination more challenging, and offers seven science-backed strategies to help you finally get unstuck.

Why ADHD Makes You Procrastinate

If you have ADHD, procrastination is practically built into the condition. ADHD affects "executive functions"—your brain's self-management systems for planning, focusing, and controlling impulses. Research shows that executive dysfunction is a core feature of ADHD, leading to difficulties with organization, sustained attention, and task initiation.

Executive Function Challenges

Adults with ADHD commonly experience difficulty organizing tasks, avoiding tasks requiring sustained mental effort, easy distractibility, and forgetfulness. Studies demonstrate that executive functions like time management and organization directly mediate the relationship between ADHD symptoms and procrastination—in other words, these executive function deficits are the bridge between having ADHD and struggling to start tasks.

The ADHD brain also seeks instant gratification and novel stimulation. Long-term projects with no immediate payoff are particularly hard to start until urgency (like an approaching deadline) finally provides that stimulation. Many people with ADHD experience "task paralysis"—feeling frozen and unable to begin a project, especially if it's large or unclear.

Executive function deficits in ADHD create real challenges with task initiation, time management, and sustained focus.

Emotional Dysregulation

ADHD involves difficulty managing emotions like boredom, frustration, and overwhelm. When a task triggers uncomfortable feelings—think of a tedious spreadsheet or overwhelming house chore—avoiding it becomes a way to escape those emotions. Research links procrastination with an inability to regulate mood: if starting a task makes you feel bad, you put it off to feel better in the moment.

Ironically, ADHD can create a double-edged sword with focus. You might experience hyperfocus on interesting activities, losing track of time while gaming or researching a hobby—leaving that important report still unwritten.

Why Anxiety Fuels Procrastination

If you struggle with anxiety, procrastination often comes from fear and avoidance. You're not lazy—you're scared: afraid of failing, afraid of criticism, or anxious that you won't do a good job. Research demonstrates that fear of failure is one of the strongest predictors of procrastination, especially when coupled with difficulties regulating emotions.

The Avoidance Cycle

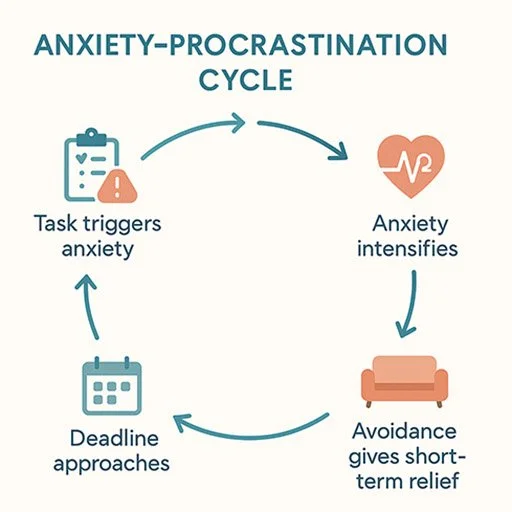

Psychologists describe this as "giving in to feel good": when a task makes you feel dread or anxiety, you find something else to do that relieves that anxiety temporarily. For example, you might suddenly start cleaning when you intended to write a difficult email—tidying feels easier than facing the potential stress. This avoidant relief is only temporary, and often you end up with even more anxiety as the deadline approaches.

Studies show that people who fear failure become anxious when asked to perform duties and try to reduce their anxiety by postponing work. This creates a vicious cycle where avoidance provides short-term relief but amplifies long-term anxiety.

The anxiety-procrastination cycle provides short-term relief but creates long-term stress and overwhelm.

Perfectionism and Analysis Paralysis

Anxiety-driven procrastination is closely tied to perfectionism and fear of failure. If you're worried you won't meet your own high standards, it might feel safer not to start at all than to risk doing poorly. You may also feel overwhelmed by everything that could go wrong, leading to analysis paralysis—spending so much time overthinking ("What if I do it wrong?") that you never actually take action.

7 Evidence-Based Strategies to Stop Procrastinating

Now that you understand why procrastination happens, let's explore concrete strategies that can help. These techniques are backed by research and address the root causes we've discussed.

1. Reframe Your Thoughts (Cognitive Restructuring)

One powerful approach from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) involves challenging the unhelpful thoughts fueling your procrastination. Research shows that CBT interventions produce large reductions in procrastination, with participants seeing improvements in depression and anxiety as well.

How to practice:

- Identify the thought: "I'll mess this up" or "I don't know where to start"

- Challenge it: Is this absolutely true? What evidence contradicts it?

- Replace it: "I can start small and learn as I go" or "I've handled challenging tasks before"

This technique is especially helpful for anxiety-driven procrastination. By catching and reframing catastrophic thoughts, you reduce the emotional intensity that makes tasks feel impossible.

2. Break Tasks Into Tiny Steps

Large, vague tasks trigger both ADHD executive dysfunction and anxiety overwhelm. The solution? Make tasks so small they feel almost trivial.

Instead of "Write report," break it down to:

- Open document (1 minute)

- Write one sentence (5 minutes)

- Draft introduction (15 minutes)

This works because it reduces the emotional and cognitive load. Each small step feels achievable, building momentum and confidence.

3. Use Time-Boxing and the Pomodoro Technique

Research specifically supports the Pomodoro Technique for people with ADHD. The standard method involves working for 25 minutes, then taking a 5-minute break. For ADHD brains, you might need to adjust this—try 15-minute work sessions or 45-minute sessions, depending on your attention span.

Why it works:

- Creates artificial urgency that activates the ADHD brain

- Prevents burnout through built-in breaks

- Makes overwhelming tasks feel manageable ("I just need to focus for 25 minutes")

- Provides a clear structure that supports executive function

The Pomodoro Technique creates manageable work intervals that prevent overwhelm and support executive function.

4. Schedule Tasks at Your Peak Energy Times

Don't fight your biology. If you have more energy and focus in the morning, schedule your most challenging tasks then. Save administrative work or easier tasks for lower-energy periods.

For people with ADHD, this is especially important—your stimulant medication timing (if you take it) should align with when you need maximum focus.

5. Practice Mindfulness to Reduce Avoidance

Multiple studies demonstrate that mindfulness training significantly reduces procrastination. One randomized controlled trial found that after eight weekly 90-minute mindfulness sessions, participants showed large reductions in procrastination behavior.

Mindfulness helps by:

- Increasing awareness of avoidance patterns

- Improving emotion regulation (the core issue in procrastination)

- Reducing anxiety about tasks

- Strengthening attention and focus

Start with just 5 minutes of meditation daily. Apps like Wellness AI can provide guided practices specifically designed for procrastination and anxiety.

6. Use Body Doubling for ADHD

Body doubling—working alongside someone else—is a surprisingly effective ADHD strategy. You don't need to work on the same task or even talk; just having another person present creates accountability and reduces distraction.

How to try it:

- Work at a coffee shop or library

- Use virtual co-working sessions (many free online)

- Ask a friend to work silently with you via video call

Research suggests this works because another person's presence provides external structure that compensates for ADHD executive function challenges.

7. Address Anxiety with Exposure and Self-Compassion

For anxiety-driven procrastination, gradually expose yourself to the feared task in small doses. If you're avoiding a difficult conversation, start by writing notes about what you want to say.

Equally important: practice self-compassion. Research suggests that self-kindness may be one of the most effective counters to procrastination. When you notice procrastination urges, try: "This feels hard. It's okay to feel stressed. I'm doing my best."

Self-criticism only amplifies shame and anxiety—the very emotions driving procrastination.

Self-compassion reduces the shame and anxiety that fuel procrastination, making it easier to take action.

When to Consider Professional Help

If procrastination significantly impacts your life despite trying these strategies, consider:

For ADHD:

- Medication evaluation (stimulants can help with executive function and task initiation)

- ADHD coaching or therapy focused on organizational skills

- Learn more about managing ADHD with mindfulness

For Anxiety:

- Therapy specializing in anxiety management

- Consider Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) which specifically addresses avoidance

- Digital tools like Wellness AI that provide 24/7 support with CBT techniques and personalized meditations

The Bottom Line

Procrastination with ADHD or anxiety isn't about laziness—it's about how your brain processes emotion, urgency, and overwhelm. By understanding these underlying mechanisms and using targeted strategies, you can break the cycle.

Start small: pick one strategy from this list and try it for a week. Notice what changes. Remember, progress matters more than perfection.

-Tim, Founder of Wellness AI

About the Author

Dr. Timothy Rubin holds a PhD in Psychology with expertise in cognitive science and AI applications in mental health. His research has been published in peer-reviewed psychology and artificial intelligence journals. Dr. Rubin founded Wellness AI to make evidence-based mental health support more accessible through technology.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is procrastination a symptom of ADHD?

Yes, procrastination is a common feature of ADHD. Studies show that procrastination is directly linked to ADHD symptoms, particularly inattention. The executive function deficits in ADHD—including difficulties with time management, organization, and sustained attention—create significant challenges with task initiation and completion.

Why do I procrastinate even on things I enjoy?

This often happens with ADHD due to "task initiation paralysis"—difficulty beginning any task, even enjoyable ones. The ADHD brain struggles with the transition from one activity to another and the mental effort required to start something new. Additionally, if you're anxious about doing the enjoyable task "right" or performing well, that fear can trigger avoidance.

Can anxiety medication help with procrastination?

Anxiety medications can help reduce the anxiety that fuels avoidance-based procrastination. However, medication works best when combined with behavioral strategies like CBT. For ADHD-related procrastination, stimulant medications may be more directly helpful as they improve executive function and task initiation. Always consult with a healthcare provider about medication decisions.

How long does it take to break procrastination habits?

Research on CBT for procrastination shows significant improvements within 8-12 weeks, with benefits often maintained at one-year follow-up. However, individual timelines vary. Consistency matters more than speed—practicing one or two strategies regularly for several weeks typically yields better results than trying everything at once.

Is procrastination the same as being lazy?

No. Procrastination and laziness are fundamentally different. Procrastination involves voluntarily delaying tasks despite knowing there will be negative consequences, and it's driven by difficulty regulating emotions like anxiety, boredom, or overwhelm. Laziness implies not caring about outcomes. People who procrastinate typically care deeply about their tasks—that's why the delay causes them stress and guilt.

Can mindfulness really help with procrastination?

Yes. Multiple randomized controlled trials show that mindfulness training reduces procrastination. One study found that eight weekly mindfulness sessions led to large reductions in procrastination behavior. Mindfulness works by improving emotion regulation, increasing present-moment awareness, and strengthening attention—all of which counter the mechanisms driving procrastination. Even brief daily practice can be beneficial.

What's the difference between ADHD procrastination and anxiety procrastination?

While both involve difficulty starting tasks, the underlying causes differ:

- ADHD procrastination stems from executive dysfunction—difficulty with planning, time management, and task initiation, plus a need for novelty and immediate reward

- Anxiety procrastination stems from fear and avoidance—worrying about failure, criticism, or not being good enough

However, these often overlap. Many people have both ADHD and anxiety, and procrastination can be driven by both executive dysfunction and fear simultaneously.

Should I tell my employer/professor about my ADHD or anxiety?

This is a personal decision based on your specific situation and needs. If your procrastination is affecting performance and you need accommodations, disclosure might be helpful. Many workplaces and schools offer accommodations for ADHD and anxiety disorders, such as extended deadlines, flexible scheduling, or reduced distractions. However, you're not obligated to disclose mental health conditions. Consider speaking with a therapist or disability services office about your options.